There are more than 500 racially restrictive covenants, which banned nonwhite people from owning and sometimes occupying homes in the city.

Mounds View moved Monday toward becoming the first city in Minnesota to require homeowners to discharge racist language in property titles before selling their homes.

These covenants were largely placed on properties before the 1960s to bar nonwhite people from buying and sometimes even occupying property. They have not been legally enforceable for decades, but remain in property records across the United States and have left scars of racial and economic segregation.

There are more than 500 racially restrictive covenants on Mounds View properties, making it the city with the second-highest number by population in 1960 in Ramsey County, following Falcon Heights, according to research by Mapping Prejudice, a University of Minnesota Libraries research project mapping the restriction. Many in Mounds View explicitly bar those “other than of the Caucasian race,” from owning or occupying the property.

Kirsten Delegard, director of Mapping Prejudice, said that while covenants aren’t enforceable they’ve had long-lasting consequences: “Neighborhoods once gated with covenants are still the whitest areas in the Twin Cities,” Delegard said.

Today, homes with covenants in Minneapolis are worth 15% more than those without, Delegard said. And these restrictions contribute to the Twin Cities having one of the largest racial home-ownership gaps in the country, she said, urging residents to consider contemporary policies that connect to that history.

In 2019, the Legislature passed a law allowing homeowners to add language to property titles that discharge racially restrictive covenants.

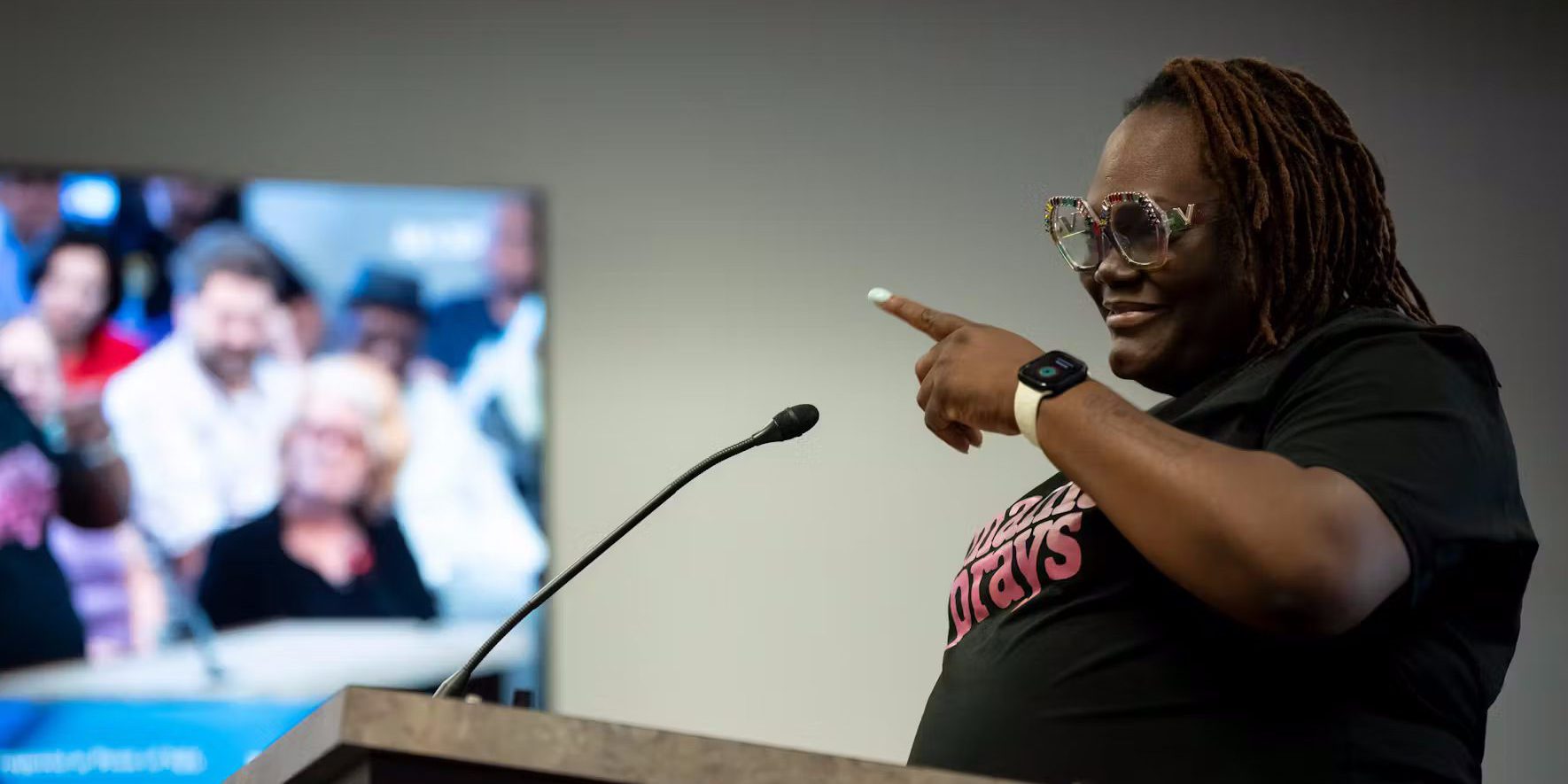

Residents cheered Monday night when the council voted unanimously to pass the ordinance requiring discharge before sale, which will get a second reading before it is final. The council also voted to join the Just Deeds coalition, a group working to educate the public about the covenants and help homeowners remove them, as well as discharge restrictive covenants found on city property.

At the hearing, many Mounds View residents spoke — all in support — of the ordinance.

Jean Strait said she was shocked to see how many racially restrictive covenants are in Mounds View. She said the language feels hateful and unwelcoming. “I urge you, as a disabled, gay, biracial person who lives in your community, we need to be free of the racist, exclusionary language,” she said.

Darnell Baker, the incoming director of Quincy House, a nonprofit that works with at-risk teens — many of them youth of color — said he was troubled to find a covenant on the land where the nonprofit sits.

City Administrator Nyle Zikmund said reception from the community has been positive. The city has sent mailings to homes with known racially restrictive covenants that include the form required to discharge them.

Mayor Zach Lindstrom, whose family wouldn’t be allowed to live in many homes in Mounds View in a different era because of racist deed language, said he was relieved by the move.

“It isn’t something that I want to have to explain to my kids,” Lindstrom told the Star Tribune last month.

A third of Mounds View residents identify as Black, Indigenous or people of color, according to census data.